Phil Stacey column: A conversation with a childhood hero

This article was originally posted on Salemnews.com By Phil Stacey Executive Sports Editor on Sep 30, 2020.

We all have childhood heroes.

Rarely, though, do we ever get the chance to meet or speak with them.

This week, I decided to rectify that.

I was able to get in touch with Fred Lynn, who played a brilliant center field for the Red Sox for six seasons from 1975-80, at his home in Southern California.

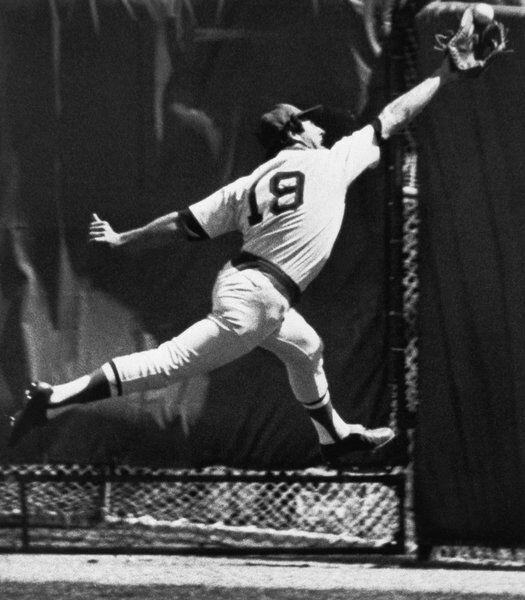

The same Fred Lynn who, along with Jim Rice, made up half of the Gold Dust Twins. Fred Lynn, the first player in baseball history to win both American League Rookie of the Year and MVP the same season (1975). Fred Lynn, he of the sweet left-handed stroke. Fred Lynn, who never met a fence he wouldn’t scale to make a catch.

Fred Lynn, the same guy who was a hero to untold baseball-loving youngsters in the Greater Boston area and beyond in the late 1970s … including this one.

“I get that a lot these days. You’re right in my demographic,” Lynn, now 67, said with a chuckle.

“The funny thing is, I was never aware of that when we were playing,” he added. “We were just baseball players; everything was pretty simple. You just played the games and that was it. I had no idea the impact that I was having on others. People come up to me now and say, ‘I named my son after you’, and that’s pretty humbling.”

Lynn’s first three seasons in Boston were nascent years for this sports-obsessed youngster; his last three at Fenway Park made me appreciate his talents, drive and all-around prowess even more so.

I didn’t just like Fred Lynn; as a fellow left-handed hitter and thrower, I wanted to be Fred Lynn in the way a child wants to emulate every aspect of his or her hero.

I made sure I got uniform top No. 19 for the Beverly Little League Colonels in the spring of 1977. I told my coaches I was a center fielder, despite not exactly being fleet of foot. I had the Wilson A2185 Fred Lynn model baseball glove, complete with a facsimile of his signature in the pocket of the mitt. I had a Louisville Slugger wooden bat, also with his signature on it, and I’d run my left hand up the barrel once and take a few practice cuts once I stepped into the batter’s box, just like he did.

When the Red Sox traded Lynn to the California Angels in January 1981, this not-quite 12-year-old wanted to cry. But I didn’t, because that’s not what ballplayers did (confirmed by Jimmy Dugan in the movies a little over a decade later).

So getting the chance to finally speak with him, I tried to remember particular nuances I always wanted to relive with him. Like when he leaped and pulled back a home run at Minnesota’s Metropolitan Stadium, robbing Disco Danny Ford of a home run in a clip that was shown forever on ‘This Week In Baseball’. Or his 5-hit, 3-homer, 10-RBI night as a rookie in Detroit. Or about how he’d dive forward, to the side or into many fences to snare a fly ball.

We laughed together when I recounted to him that, as a youngster, I told my father Ted Williams wasn’t the last man to bat .400; it was Fred Lynn, because it said so right on the back of his 1976 Topps baseball card (he hit .419 in 15 games as a September 1974 callup to the big leagues).

“I never felt pressure from outside sources,” said Lynn. “I put enough on myself. I expected to do well all the time. My attitude was always to do the best I can each day with what I had that particular day, and try to put my team in a position to win.”

He told me things I never knew, such as how finding the multitude of ponds and lakes around New England was his release from playing in the fishbowl of Boston. Lynn said he never kept any of his own memorabilia, and almost all of what he now owns has been given to him. Being “a pretty loyal guy”, he figured he’d be with the Red Sox forever, but when he was dealt “it was a slap upside the head that there’s a business side to the game.”

I also never knew that he was self admittedly shy “pretty much throughout my career, to be honest.” It wasn’t until his wife Natalie, who worked in TV sales in the Boston area, taught him how to project and emote while getting him ready for a job in baseball broadcasting. “She’s a big influence on my personality and who I am today,” he said of his wife of 34 years.

With an ever-present smile on his face, Lynn said he loves hearing from and interacting with Red Sox fans. He and Natalie come back to Boston four times a year and play host in the 20-person Legends Suite, situated just behind home plate. Because of the coronavirus pandemic he wasn’t able to do so this summer and “absolutely missed seeing our friends and the 1-on-1 interaction with fans”, but stays busy on Cameo.com by sending folks birthday and anniversary wishes, among others.

Lynn feels that better days are ahead for the Red Sox provided they can fix their pitching woes; he likes what he’s seen from rookie Tanner Houck. He said he’ll be rooting for the Padres (one of 4 teams he played for after the Red Sox) this postseason, and he’s excited to get back to Fenway in 2021 if it’s safe to do so. Then we said goodbye.

Now in my 31st year in the sportswriting business, I stopped being awed by pro athletes many, many moons ago.

But hey, rules are made to be broken on rare occasions. This was Fred Lynn, after all.

###

Phil Stacey is the Executive Sports Editor of The Salem News. Contact him at pstacey@salemnews.com, and follow him on Twitter @PhilStacey_SN